Provocateur -n

We didn’t have much growing up. My father left when I was seven and my mom was left to pinch pennies and cut coupons and provide for herself, my younger sister, and I. Hamburger Helper, or macaroni and cheese with tuna and peas. Thrift store clothes, K-Mart shoes. Knock off brand everything. She kept the heat at 60 in the dead of Southwest Colorado winter. Things got a little easier when my mom’s developmentally delayed sister moved in and suddenly there was an in-house babysitter which allowed my mom to take extra shifts at work, or side jobs as she heard about them.

It was a shock to realize that Hamburger Helper could actually have hamburger in it.

The furniture was cobbled together from what my mom could find in the newspaper after my father took their marital set. A menagerie of orphaned bowls and plates filled the cupboards. Washed salsa and jam jars stood in for glasses. There were chips in the casserole dish, the Crock Pot was my grandmother’s from time immemorial, and my mom drove a baby shit brown 1980 Toyota Corona. No, not a Corolla. A Corona.

But somehow, we had an American Heritage English Dictionary. Hardcover. Two thick volumes, 500 pages each, their vermillion covers with gold flake letter press bound together in a clear plastic sleeve. We kept the behemoth alone on a shelf on the entertainment unit where one could, if one were so inclined, flip through it leisurely. No one ever did, but the option was there. That is to say that the dictionary held a place of honor in our house, but it did not receive any honor.

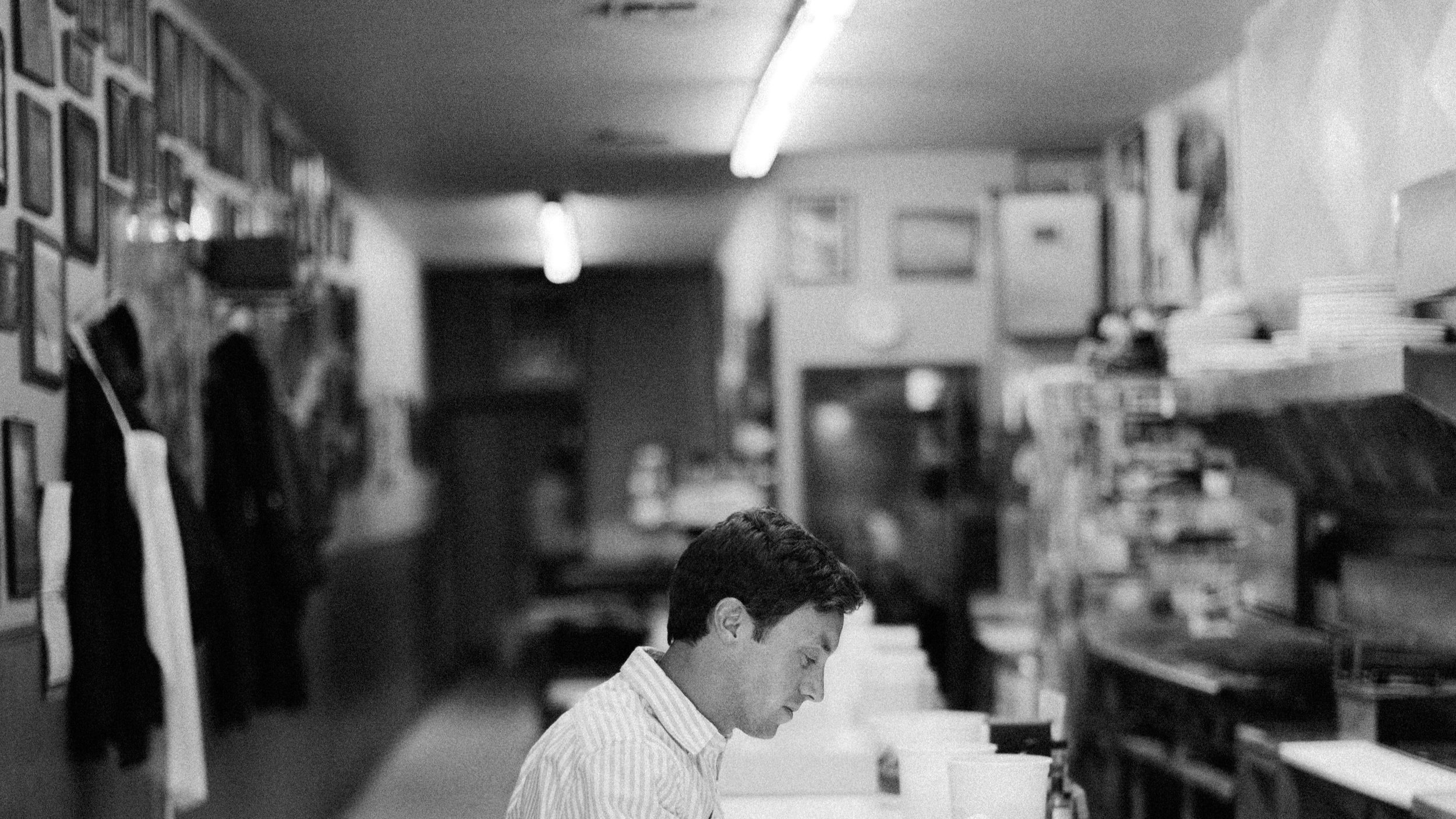

That began to change when Eric moved in after dating my mom for a year. He arrived with a duffle bag’s worth of clothes, a baseball glove tucked neatly underneath the handles of that duffle bag, and boxes of books. Boxes of fiction: The Count of Monte Cristo, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Moby Dick, The Scarlet Letter. Boxes from his collegiate studies: Modern Principles of Economics, The Wealth of Nations, Capitalism and Freedom, The Affluent Society. Boxes of non-fiction. A Brief History of Time, Walden, Confessions, The Republic. The mailbox began to receive The Atlantic, Sports Illustrated, The Economist, and Forbes. When he drove us to school in the morning, we listened to Paul Harvey or the morning news. After dinner, he sat on the couch and read and he didn’t mind if my sister or I joined him. When my father was around, the TV was always on. When he moved out and it was just my mom, my sister, and I, the radio was always on. With Eric, words were everywhere.

“An old aphorism comes to mind…” Paul Harvey would say, and my ears would perk up and the back of my neck would prickle with heat.

“Eric, what’s an aphorism?”

“I don’t know. Look it up.”

And this became the response to everything. Every time I heard or read a new word, I would ask Eric what the word meant and he would respond without fail, “I don’t know. Look it up.” At first, I was irritated by this response. Clearly he knew what the word meant. Why wouldn’t he just tell me? The dictionary was so big, so looming, so intimidating. And we didn’t have a smaller one. It was a mammoth undertaking to get the top volume off of the bottom. But the words kept coming, and Eric kept telling me he didn’t know what they meant. So I looked the words up. Again and again and again. Sometimes I would have to keep a list of words to look up when I got home. Sometimes that list was long. The dictionary and I became friends. More than friends. Compatriots, colleagues, comrades, confidantes. I liked collecting words and having them bounce around in my head, but it was a collection without context or utility. Sort of like knowing a fun fact that doesn’t bear any relevance to the conversation at hand.

And then came the day that the dictionary and I went from confidantes to co-conspirators.

One night, we were having dinner and my sister was either poking me in the arm or trying to steal my food or moving my plate around or elbowing me or any of the countless things that a little sister can and will and ought to do to their older brothers and Eric, in his calm, imperturbable way said, “Caitlyn, stop being a provocateur.”

The aperture of my mind opened wide and light flooded in, completely overwhelming any sense of anything that had been before. I couldn’t feel my face. I couldn’t remember my own name. Until this point, words were breaths. Things that happened reflexively. That just were. But there was something different about this word. My ears did not merely perk up. They jumped. As though they were trying to reach for the air in which the word hung. My skin did not merely prickle with heat. No, now there was a conflagration at the base of my neck and rising steadily. A fever that reached my temples and then my cheeks.

I didn’t even ask the question. I didn’t ask to be excused. I hopped up and ran to what once had been a shelf, but now was only recognizable to me as an altar. I knelt before it. I threw the top volume over with a loud thump and tore open the second volume. S—, too far. Flip flip flip. P— okay, Pr— okay okay, Pro—

“Eric! P—R—O—V— A or O?!”

“O.”

provocateur - noun

pro· vo· ca· teur (prō-ˌvä-kə-ˈtər )

1 : AGENT PROVOCATEUR (from the French)

2 : one who provokes (a political provocateur)

3 : a person who provokes trouble, causes dissension, or the like; agitator.

It was an epiphany. An awakening. A religious experience. I looked around the room to see where God had landed, because surely He was there. A person who provokes trouble, causes dissension, or the like; agitator. In one word. This was stunning. Confounding. Flabbergasting. Nonplussing. The implications, of course, were immense and the room began to spin slightly, and while I deeply wish that my little 9 year old brain had thought of how wonderous language is and how specific it can be and about how incredible it is that we can communicate any idea at all with the sheer amount of words and meanings there are out there, it only had room for one enormously attractive (and a little evil) thought: I can say whatever I want to someone— call them anything I want— without them knowing any better.

I returned to the table and fell into the chair as though I’d just run a marathon. Eric was smirking and had his arms crossed against his chest and asked me what the word meant. I told him. He seemed very satisfied. As though he knew what he’d done. As though he knew he’d opened Pandora’s Box. But he didn’t know. Couldn’t have. He didn’t then and doesn’t now know how much that moment has profoundly shaped my life. He only knows that now when we talk, he has to stop me occasionally and ask me just “what in the blue fuck does that word mean?”

Sometimes I’m tempted to tell him that I don’t know and that he should look it up.